Enjeux et débats des humanités numériques

Debates in the Digital Humanities

Enjeux

- Enjeux épistémologiques

- Enjeux politiques

Enjeux épistémologiques

- Le réductionnisme inhérent aux méthodes computationnelles

- Absence - supposée ou réelle - de résultats

- Arbitraire théorique et manque de rigueur

Stephen Marche, « Literature is not Data: Against Digital Humanities »

Adam Kirsch, « Technology is Taking Over English Departments » (1)

Humanistic thinking does not proceed by experiments that yield results; it is a matter of mental experiences, provoked by works of art and history, that expand the range of one’s understanding and sympathy. It makes no sense to accelerate the work of thinking by delegating it to a computer when it is precisely the experience of thought that constitutes the substance of a humanistic education. The humanities cannot take place in seconds.

La recherche dans les humanités ne s'appuient pas sur des expériences qui donnent des résultats : elle s'appuie sur des expériences mentales [mental experiences] provoquées par l'histoire et les oeuvres d'art, expériences qui bonifient notre capacité de compréhension et notre empathie (ou compassion —> sympathy). Cela ne sert à rien d'accélérer le travail de réflexion en le déléguant à un ordinateur puisque c'est précisément ce travail qui est à la base des humanités. Celles-ci ne peuvent avoir lieu, ne peuvent se dérouler [take place] en quelques secondes.

Timothy Brennan, « The Digital Humanities Bust » (1)

Distant readers are not wrong to say that no human being can possibly read the 3,346 novels that Matthew L. Jocker […] has machines do in Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History. But they never really say why they think computers can. Compared with the brute optical scanning of distant reading, human reading is symphonic -- a mixture of subliminal speaking, note-taking, savoring, and associating. Computer circuits may be lightning-fast, but they preclude random redirections of inquiry. [...] DH offers us powerful but dull tools, like a weightlifter doing a pirouette.

Ceux qui pratiquent le distant-reading n'ont pas tort lorsqu'ils affirment qu'il n'y a aucun humain qui pourrait lire les 3 346 romans que Jockers fait lire à des machines dans Macroanalysis. Mais ils ne disent jamais vraiment pourquoi ils croient que des ordinateurs en sont capables. Comparée au balayage optique grossier du distant-reading, la lecture humaine est symphonique — un mélange de discours subliminal, de prises de notes, d'appréciation et d'association. Les circuits d'ordinateurs sont peut-être rapides comme l'éclair, mais ils empêchent les détours aléatoires [random redirections] dans l'analyse. […] Les humanités numériques nous offrent des outils puissants, mais sans intérêt, tel un haltérophile exécutant une pirouette.

Timothy Brennan, « The Digital Humanities Bust » (2)

Ted Underwood, the Illinois professor, finds "interesting things" when tracing word frequencies in stories but does not say what they are -- a typical gesture in DH literature. Similarly, Alexander Galloway, a professor of media, culture, and communication at New York University, accepts that word frequencies in Melville are significant: "If you count words in Moby-Dick, are you going to learn more about the white whale? I think you probably can -- and we have to acknowledge that." But why should we? The significance of the appearance of the word "whale" (say, 1,700 times) is precisely this: the appearance of the world "whale" 1,700 times.

Ted Underwood, le professeur de l'Université de l'Illinois, trouvent des « choses intéressantes » en calculant des fréquences de mots dans des récits, mais ne dit pas ce qu'elles sont — une façon de faire typique des travaux en humanités numériques. De façon similaire, Alexander Galloway […] accepte que les fréquences de mots dans Melville sont signifiantes : « Si on compte les mots dans Moby Dick, est-ce qu'on apprend quelque chose de plus sur la baleine blanche ? Je crois que c'est possible — et on doit prendre en compte cet état de fait. » Mais, pourquoi devrait-on ? Le sens de l'apparition du mot « baleine » (disons, 1 700 fois) ne veut dire que ceci : ce mot apparaît 1 700 fois.

Adam Kirsch, « Technology is Taking Over English Departments »

The language here is the language of scholarship, but the spirit is the spirit of salesmanship—the very same kind of hyperbolic, hard-sell approach we are so accustomed to hearing about the Internet, or about Apple’s latest utterly revolutionary product. Fundamental to this kind of persuasion is the undertone of menace, the threat of historical illegitimacy and obsolescence. Here is the future, we are made to understand: we can either get on board or stand athwart it and get run over. The same kind of revolutionary rhetoric appears again and again in the new books on the digital humanities, from writers with very different degrees of scholarly commitment and intellectual sophistication.

La langue est celle de la recherche, mais l'esprit est celui du marketing -- la même approche hyperbolique à laquelle nous sommes habitués lorsqu'on entend parler d'Internet ou du dernier produit révolutionnaire d'Apple. Ce genre d'argumentaire s'appuie de façon fondamentale sur la menace de l'obsolescence et de l'illégitimité historique. Ce qu'on veut nous faire comprendre, c'est qu'il est là, le futur : on peut embarquer ou s'y opposer et se faire rouler dessus. Ce genre de rhétorique est une constante des nouveaux ouvrages en humanités numériques […].

Timothy Brennan, « The Digital Humanities Bust » (3)

As often happens in computational schemes, DH researchers shrink their inquiries to make them manageable. For example, to build a baseline standard of what constitutes quality, So and Piper posit that "literary excellence" be equated with being reviewed in The New York Times. Such an arbitrary standard would not withstand scrutiny in a non-DH essay. The disturbing possibility is not only that this "cheat" is given a pass (the aura of digital exactness foils the reproaches of laymen), but also that DH methods -- operating across incompatible registers of quality and quantity -- demand empty signifiers of this sort to set the machine in motion.

Les chercheurs en humanités numériques réduisent leurs analyses pour les rendre gérables. Par exemple, pour définir un étalon de mesure de la qualité littéraire, So et Piper affirment que celle-ci peut être assimilée à faire l'objet d'une critique dans le New York Times. Un tel standard complètement arbitraire ne résisterait pas à la critique dans un article non-HN. Ce qui est inquiétant, ici, ce n'est pas seulement qu'on laisse passer cette « tricherie » [...], mais aussi que les méthodes des humanités numériques - qui agissent sur des registres incompatibles de qualité et de quantité - requièrent des signifiants vides de ce genre pour que la machine puisse être mise en marche.

Mark Sample, « Difficult Thinking »

In nearly every case, the accounts eliminate complexity by leaving out history, ignoring counterexamples, and—in extreme examples—insisting that any other discourse about the digital humanities is invalid because it fails to take into consideration that particular account’s perspective. Here facile thinking masterfully (yes, facile thinking can be masterful) twists the greatest strength of difficult thinking—appreciating multiple perspectives, but inevitably not all perspectives—into its fatal weakness. […] The problem is that so often the facile thinking about the digital humanities is not focused on our actual work, but rather on some abstract “construct” called the digital humanities.

Dans à peu près tous ces textes, on élimine la complexité en faisant l'économie de l'histoire du champ, en ignorant les contre-exemples et, dans les cas extrêmes, en affirmant que tout autre discours à propos des humanités numériques est invalide parce qu'il ignore la perspective présentée. […] Le problème est que, la plupart du temps, la pensée facile concernant les humanités numériques ne cible pas notre recherche réelle, mais bien plutôt une construction abstraite qu'ils nomment les humanités numériques.

Enjeux politiques

- Néo-libéralisme et humanités numériques

- #TransformDH

- Hégémonie anglo-saxonne

HN et néolibéralisme (1)

[T]he unparalleled level of material support that Digital Humanities has received suggests that its most significant contribution to academic politics may lie in its (perhaps unintentional) facilitation of the neoliberal takeover of the university.

Le niveau inouï d'appui financier reçu par cette discipline nous mène à penser que sa plus importante contribution à la politique de la recherche consiste en sa [peut-être involontaire] facilitation de la conquête de l'université par le néolibéralisme.

HN et néolibéralisme (2)

[I]t is not the “traditional” scholarly world, with its hierarchies and glorified experts and close reading of works read by only a precious few people, to which the Digital Humanities social movement is most meaningfully opposed. What it stands in opposition to, rather, is the insistence that academic work should be critical, and that there is, after all, no work and no way to be in the world that is not political. […] Indeed, the institutional success of Digital Humanities appears to be explained in large part by its designed-in potential to drive social, cultural, and political critique from the humanities as a whole.

Ce n'est pas à l'univers de la recherche « traditionnelle », avec ses hiérarchies, ses experts glorifiés et sa lecture rapprochée d'oeuvres lues par seulement quelques personnes, que les humanités numériques s'opposent de la façon la plus significative. Ce à quoi elles s'opposent vraiment c'est à l'idée selon laquelle la recherche doit être critique et qu'il n'y a pas, après tout, de façon de travailler et d'être dans le monde qui n'est pas politique. […] En effet, le succès institutionnel des humanités numériques peut être expliqué par son inhérente capacité à chasser la critique sociale, culturelle et politique des humanités dans leur ensemble.

HN et néolibéralisme (3)

[M]uch work in the digital humanities involves either detourning commercial tools and products for scholarly purposes or building open-access archives, databases, and platforms that resist the pressure to commercialize, as Alan Liu points out. That is why DH projects (including my own) are so often broken, nonworking, or unfinished (Brown et al.), and far from anything “immediately usable by industry,” as the authors of the LARB piece suggest. In fact, from a managerial perspective, the kind of computationally expensive uses to which digital humanists typically put technologies—such as running topic models on large corpora for hours or days on end in the hope of discovering new discursive patterns for interpretation—would appear to be an impractical and inefficient tax on resources with no immediate application or return on investment.

Beaucoup de travaux en humanités numériques impliquent le détournement d'outils et de produits commerciaux pour les besoins de la recherche ou la mise en place d'archives ouvertes, de bases de données et de plateformes qui résistent à la pression commerciale. C'est pourquoi les projets en humanités numériques sont si souvent brisés, non fonctionnels ou inachevés et loins de quelque chose qui serait immédiatement récupérable par l'industrie […]. En fait, d'un point de vue administratif, le genre d'utilisation qui est faite des ressources informatiques par les humanités numériques serait considéré comme inexploitable et inefficace.

Torn Apart / Separados

#TransformDH

Roger Whitson

Do we really need guerrilla movements? Are war metaphors, or concepts of overturning and redefining, truly the right kind of metaphors to use when talking about change in the digital humanities?

A-t-on vraiment besoin de mouvements de guérilla ? Est-ce que les métaphores guerrières ou les concepts de renversement ou de redéfinition sont vraiment le genre de métaphores à utiliser lorsqu'on veut parler de changement dans les humanités numériques ?

Alexis Lothian et Amanda Philipps, « Can Digital Humanities mean Transformative Critique »

[W]e wonder how digital practices and projects might participate in more radical processes of transformation––might rattle the poles of the big tent rather than slip seamlessly into it. To that end, we are interested in digital scholarship that takes aim at the more deeply rooted traditions of the academy: its commitment to the works of white men, living and dead; its overvaluation of Western and colonial perspectives on (and in) culture; its reproduction of heteropatriarchal generational structures. Perhaps we should inhabit, rather than eradicate, the status of bugs––even of viruses—in the system.

Nous nous demandons comment les pratiques et projets numériques pourraient participer à des processus plus radicaux de transformation, pourraient ébranler les poteaux de la grande tente plutôt que de s'y insérer fluidement. Dans ce but, nous nous intéressons à la recherche numérique qui cible les traditions les plus enracinées de la recherche : son engagement envers les oeuvres d'hommes blancs, vivants et décédés, sa survalorisation des perspectives occidentales et coloniales sur et dans la culture, sa reproduction des structures générationnelles hétéropatriarcales. Peut-être devrions-nous incarner, plutôt qu'éradiquer, le statut de bogues - et même de virus - dans le système.

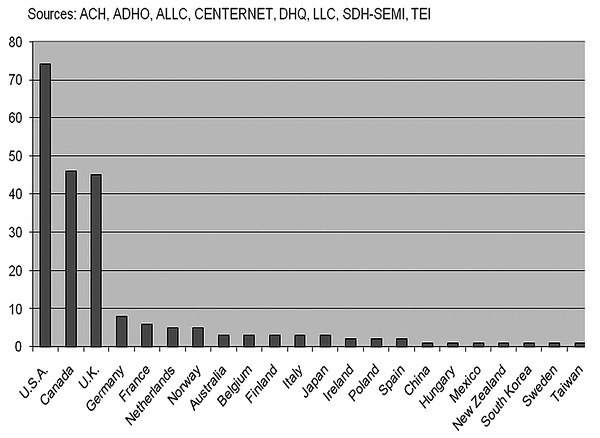

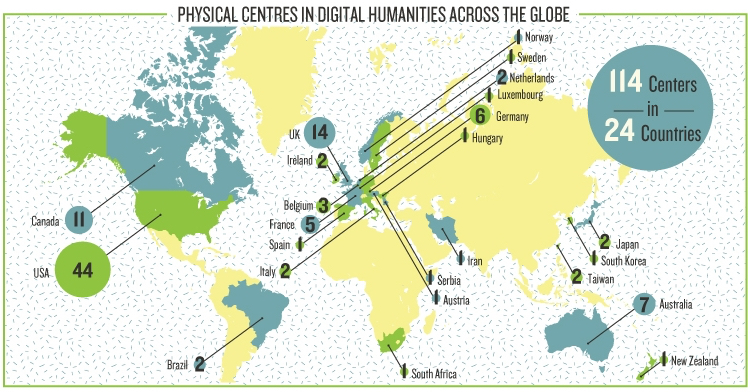

La domination de la sphère anglo-saxonne (1)

Digital Humanities, though claiming to be new and revolutionary, are structured in a very classical way for an academic field, where those who master the english language and the english speaking and impact factor based academic journals are the most visible (and the most quoted).

Les humanités numériques, bien qu'elles affirment être nouvelles et révolutionnaires, sont structurées de façon très traditionnelle pour un champ de recherche : ceux qui maîtrisent la langue anglaise […] sont les plus visibles et les plus cités.

La domination de la sphère anglo-saxonne (2)

La domination de la sphère anglo-saxonne (3)