Définition(s) et histoire des humanités numériques

Les définitions des HN, un genre en soi (1)

What is (or are) the “digital humanities,” aka “humanities computing”? It’s tempting to say that whoever asks the question has not gone looking very hard for an answer. “What is digital humanities?” essays like this one are already genre pieces.

Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, « What Is Digital Humanities and What’s It Doing in English Departments? », dans ADE Bulletin, no 150 (2010), p. 55.Les définitions des HN, un genre en soi (2)

Melissa Terras, Julianne Nyhan & Edward VanHoutte (dir.), Defining Digital Humanities. A Reader, Surrey, Ashgate, 2013.

Melissa Terras, Julianne Nyhan & Edward VanHoutte (dir.), Defining Digital Humanities. A Reader, Surrey, Ashgate, 2013.

Quelques définitions des HN

Dominique Vinck (2016)

Les humanités numériques, c'est une affaire de lettreux qui jouent aux geeks.

Dominique Vinck, Humanités Numériques. La culture face aux nouvelles technologies, Le Cavalier Bleu éditions, 2016, p. 47.Elena Pierazzo (2011)

Digital Humanities is the discipline born from the intersection between humanities scholarship and computational technologies. It aims at investigating how digital methodologies can be used to enhance research in disciplines such as History, Literature, Languages, Art History, Music, Cultural Studies and many others. Digital Humanities holds a very strong practical component as it includes the concrete creation of digital resources for the study of specific disciplines.

Elena Pierazzo, « Digital humanities: a definition ». En ligne : http://epierazzo.blogspot.co.uk/2011/01/digital‐humanities‐definition.htmlJohn Unsworth (2002)

[O]ne of the many things you can do with computers is something that I would call humanities computing, in which the computer is used as a tool for modeling humanities data and our understanding of it, and that activity is entirely distinct from using the computer when it models the typewriter, or the telephone, or the phonograph, or any of the many other things it can be.

John Unsworth, « What is Humanities Computing and What is Not? », dans Jahrbuch für Computerphilologie, no 4 (2002), p. 71.Milad Douehei (2011)

Digital Humanities est le terme courant qualifiant les efforts multiples et divers de l'adaptation à la culture numérique du monde savant.

Milad Douehei, Pour un humanisme numérique, Seuil, 2011, p. 22.Matthew G. Kirschenbaum (2015)

If digital humanities is to concern itself with the full sweep of our collective past then it must, like a Klein bottle, also come to terms with the born-digital objects and artifacts that characterize cultural production in all areas of human endeavour in the decades since the advent of general-purpose computers.

Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, « Ancient evenings : Retrocomputing in the Digital Humanities », dans Susan Schreibman et al. (dir.), A New Companion to Digital Humanities, Wiley-Blackwell, 2e édition, 2016, p. 188.Stephen Ramsay (2011) (1)

Nowadays, the term can mean anything from media studies to electronic art, from data mining to edutech, from scholarly editing to anarchic blogging, while inviting code junkies, digital artists, standards wonks, transhumanists, game theorists, free culture advocates, archivists, librarians, and edupunks under its capacious canvas.

Stephen Ramsay, « Who's in and Who's Out », dans Melissa Terras, Julianne Nyhan & Edward VanHoutte (dir.), Defining Digital Humanities. A Reader, Surrey, Ashgate, 2013, p. 239-243.Stephen Ramsay (2011) (2)

Do you have to know how to code [to be a digital humanist]? I’m a tenured professor of digital humanities and I say “yes”. [...] Personally, I think Digital Humanities is about building things. I’m willing to entertain highly expansive definitions of what it means to build something […] but if you are not making anything, you are not […] a digital humanist. You might be something else that is good and worthy – maybe you’re a scholar of new media, or maybe a game theorist, or maybe a classicist with a blog (the latter being a very good thing indeed) – but if you aren’t building, you are not engaged in the “methodologization” of the humanities, which, to me, is the hallmark of the discipline that was already decades old when I came to it.

Stephen Ramsay, « Who's in and Who's Out ». 8 janvier 2011. http://stephenramsay.us/ text/2011/01/08/whos-in-and-whos-out.html.L'histoire des HN

- Les origines : 1949-1969

- La constitution des premiers grands corpus : 1970-1983

- L'ordinateur personnel et la création de la TEI : 1984-1992

- Le développement du web : 1993-2003

- Les HN aujourd'hui : 2004-

Les origines : 1949-1969

1949 - Roberto Busa débute la mise en place du Corpus Thomisticum

1964 - Création du Centre for Literary and Linguistic Computing

Les authorship studies

- Un des premiers types d'analyse textuelle automatisée

- Un exemple : Andrew Morton et son travail sur les épîtres pauliniennes (1963)

Septembre 1966 - Parution du premier numéro de Computers and the Humanities

Les humanities computing en France : l'École des Annales

- Plusieurs travaux de recherche menés au milieu des années soixante à l'aide de l'informatique.

- Un exemple : Les Paysans du Languedoc d'Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie.

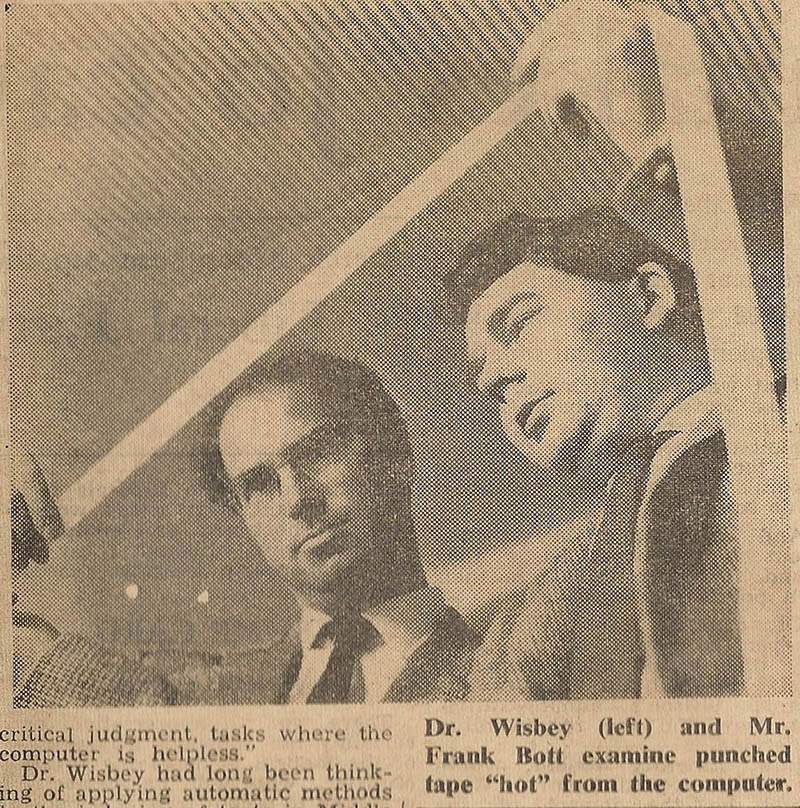

Fin des années 60 - Création du logiciel et du format de fichier textuel COCOA

- 4000 cartes perforées

- Permet la création d'index et le comptage de mots

- L'usager peut spécifier la structure du document ciblé et faire se chevaucher plusieurs structures textuelles (texte + métadonnées)

La constitution des premiers grands corpus : 1970-1983

1972 - Création du Thesaurus Linguae Graecae

1976 - Création de la Oxford Text Archive (OTA)

- Premier dépôt d'éditions électroniques de textes pour la recherche

- Fondateur : Lou Burnard

En France, création de Frantext

- Encodage de 1000 textes français

- Pour servir d'exemples pour Le Trésor de la langue française

Création des premières associations, des premiers événements HN

- En Grande-Bretagne : tenue, à partir de 1970, de conférences annuelles qui découleront sur la mise en place de l'Association for Literary and Linguistic computing (1973)

- Aux États-Unis : mise en place des International Conferences on Computing in the Humanities qui inspireront la création, en 1978, de l'Association for Computers and the Humanities

1982 - Le Oxford Concordance Program (OCP) supplante COCOA

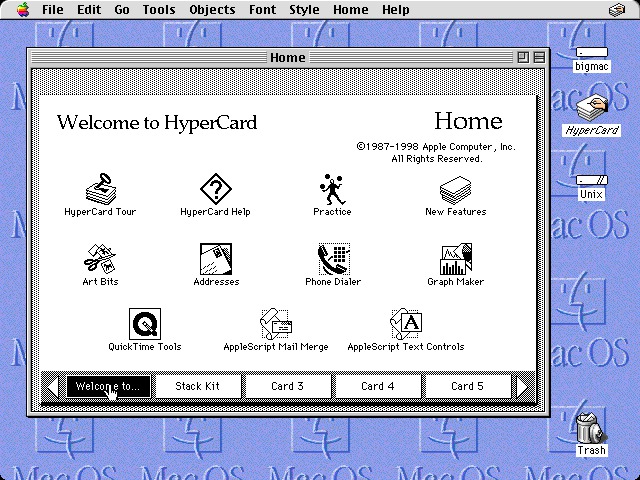

L'ordinateur personnel, HyperCard, le courriel et la création de la TEI : 1984-1992

1987, 1990 - Hypercard et Hypercard 2.0

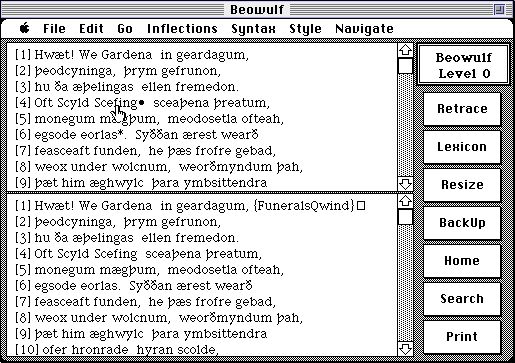

1991 - Beowulf Workstation

Adoption massive de la technologie du courriel

- La majorité des universités donnent accès à ce service à partir du milieu des années quatre-vingt

- Facilite fortement les échanges entre les chercheurs en HN et, de fait, la diffusion des innovations technologiques

Des publications importantes

- 1986 - Début de la parution de Literary and Linguistic Computing

- 1988 et 1989, les Humanities Computing Yearbook

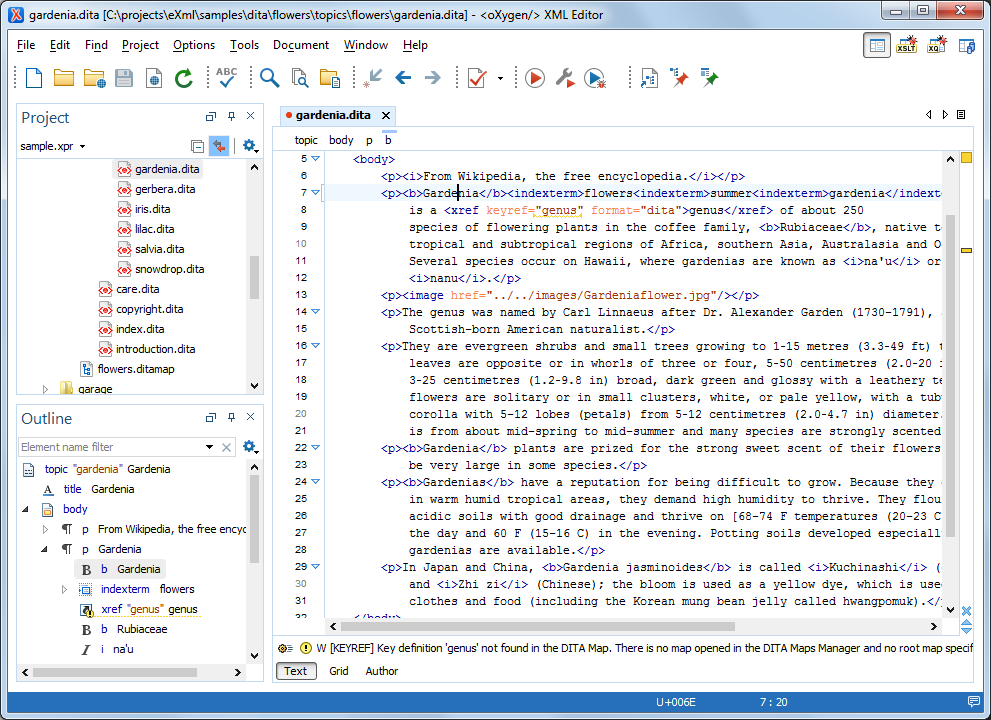

Novembre 1987 - Création de la TEI

- Mise en place d'une norme d'encodage des textes

- Mai 1994 - Première version (P1) des Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange

XML/TEI (1) - Oxygen

XML-TEI (2)

<div type="edition">

<head>Text</head>

<ab subtype="text" n="2">Text II

<lb xml:id="line_1" n="1"/><name type="animal" key="goat">

<w lemma="αἴξ">αἲξ</w></name> <name type="sacrifice">

<w lemma="θύω">θύεται</w></name>.

<lb/><space quantity="1" unit="line"/>

<lb/><space quantity="1" unit="line"/>

<lb/><space quantity="1" unit="line"/>

</ab>

<ab subtype="text" n="1">Text I

<lb xml:id="line_2" n="2"/><w lemma="ὅδε">τάδε</w> <w lemma="μή">μὴ</w>

<w lemma="εἰσφέρω">ἐσφέρεν</w> <w lemma="εἰς">ἐς</w> τὸ

<lb xml:id="line_3" n="3"/><name type="structure"><w lemma="τέμενος">τέμενος</w>

</name> τοῦ <name type="deity" key="Apollo"><w lemma="Ἀπόλλων">Ἀπόλλω

<lb xml:id="line_4" n="4" break="no"/><supplied reason="lost">νος</supplied>

</w></name> τοῦ <name type="epithet" key="Oulios">

<w lemma="οὔλιος">Οὐλίου</w></name>· <name type="clothing">

<w lemma="ἱμάτιον">εἱμάτιον</w></name>

<lb/><gap reason="lost" unit="line" extent="unknown"/>

</ab>

</div>

« Regulation concerning the sanctuary of Apollo Oulios at Isthmos on Kos, with an additional sacrificial regulation », projet CGRN (Fiche 101). En ligne. URL : http://cgrn.ulg.ac.be/file/101.

XML-TEI (3)

<text>

<front>

<div>

<head>Préface de l’auteur</head>

<p>Les <hi rend="i">Rougon-Macquart</hi> doivent se composer d’une vingtaine de romans.

Depuis 1869, le plan général est arrêté, et je le suis avec une rigueur extrême.

L’Assommoir est venu à son heure, je l’ai écrit, comme j’écrirai les autres,

sans me déranger une seconde de ma ligne droite. C’est ce qui fait ma force.

J’ai un but auquel je vais.</p>

<p>Lorsque L’<hi rend="i">Assommoir</hi> a paru dans un journal, il a été attaqué

avec une brutalité sans exemple, dénoncé, chargé de tous les crimes.

Est-il bien nécessaire d’expliquer ici, en quelques lignes, mes intentions d’écrivain ?

J’ai voulu peindre la déchéance fatale d’une famille ouvrière, dans le milieu empesté de nos faubourgs.

Au bout de l’ivrognerie et de la fainéantise, il y a le relâchement des liens de la famille,

les ordures de la promiscuité, l’oubli progressif des sentiments honnêtes, puis comme dénouement la honte et la mort.

C’est la morale en action, simplement.</p>

<p>L’<hi rend="i">Assommoir</hi> est à coup sûr le plus chaste de mes livres.

Souvent j’ai dû toucher à des plaies autrement épouvantables. La forme seule a effaré.

On s’est fâché contre les mots. Mon crime est d’avoir eu la langue du peuple.

Ah ! la forme, là est le grand crime ! Des dictionnaires de cette langue existent pourtant,

des lettrés l’étudient et jouissent de sa verdeur, de l’imprévu et de la force de ses images.

Elle est un régal pour les grammairiens fureteurs. N’importe, personne n’a entrevu que ma volonté

était de faire un travail purement philologique, que je crois d’un vif intérêt historique et social.</p>

<p>Je ne me défends pas d’ailleurs. Mon œuvre me défendra. C’est une œuvre de vérité, le premier roman sur le peuple,

qui ne mente pas et qui ait l’odeur du peuple. Et il ne faut point conclure que le peuple tout entier est mauvais,

car mes personnages ne sont pas mauvais, ils ne sont qu’ignorants et gâtés par le milieu de rude besogne

et de misère où ils vivent. Seulement, il faudrait lire mes romans, les comprendre, voir nettement leur ensemble,

avant de porter les jugements tout faits, grotesques et odieux, qui circulent sur ma personne et sur mes œuvres.

Ah ! si l’on savait combien mes amis s’égayent de la légende stupéfiante dont on amuse la foule !

Si l’on savait combien le buveur de sang, le romancier féroce, est un digne bourgeois, un homme d’étude et d’art,

vivant sagement dans son coin, et dont l’unique ambition est de laisser une œuvre aussi large

et aussi vivante qu’il pourra ! Je ne démens aucun conte, je travaille,

je m’en remets au temps et à la bonne foi publique pour me découvrir enfin sous l’amas des sottises entassées.</p>

<p rend="right noindent">ÉMILE ZOLA</p>

<p>Paris, 1<hi rend="sup">er</hi> janvier 1877.</p>

</div>

</front>

</text>

Émile Zola, L'Assomoir, édition numérique créée par l'Obvil.

XML-TEI (4)

[T]he size of the TEI community is limited by the complexity of the data model and the tools required to implement it, with the result that simpler, procedurally oriented text editing systems such as wikis and Wordpress have garnered more mainstream scholarly users. When what the average scholar wants above all is usability in scholarly tools and interoperability in scholarly resources, there is a tension between more usable technologies and those based on better data models and best practices.

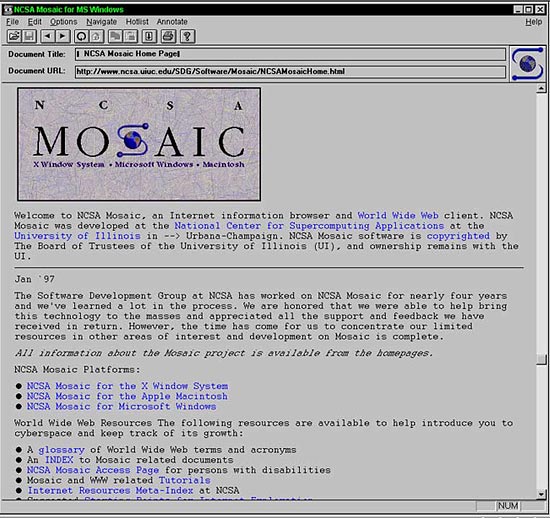

Le développement du web : 1993-2003

1993 - Le navigateur Mosaic et le World Wide Web

Multiplication des projets d'édition numérique et mise en ligne des corpus

- 1996 - William Blake Archive

- 1997 - The Orlando Project

- 1998 - Frantext

- 2001 - Thesaurus Linguae Graecae

Fin des années 90 - Premiers cursus en humanités numériques

- Diplômes en humanities computing - King's College

- M.A. en Digital Humanities - Université de Virginie (2001)

2002 - La création de l'Alliance of Digital humanities organization (ADHO)

- Regroupe de nombreuses associations HN

- Interprété par plusieurs comme un signe de maturité du champ

Les HN aujourd'hui : 2004-

Les Companions (1)

2004 - A Companion to Digital Humanities

Des Humanities computing aux Digital humanities

The real origin of that term [digital humanities] was in conversation with Andrew McNeillie, the original acquiring editor for the Blackwell Companion to Digital Humanities.[...] Ray [Siemens] wanted “A Companion to Humanities Computing” as that was the term commonly used at that point; the editorial and marketing folks at Blackwell wanted “Companion to Digitized Humanities.” I suggested “Companion to Digital Humanities” to shift the emphasis away from simple digitization.

Matthew Kirschenbaum, « What Is Digital Humanities and What’s It Doing in English Departments? », dans Debates in the Digital humanities, 2012. En ligne. http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/38Les Companions (2)

2008 - A Companion to Digital Literary Studies

Élargissement du champ

Un exemple : Les Platform studies

Les Companions (3)

2016 - A New companion to Digital Humanities

Nouvelles collections, nouvelles revues

- Collection « Digital research in the arts and humanities », chez Ashgate

- Collection « Topics in the Digital Humanities », chez Illinois Press

- Revue Digital Humanities Quarterly (depuis 2007)

- Revue Digital Studies/Le champ numérique (depuis 2009)

- Revue Journal of Digital Humanities (depuis 2012)

Multiplication d'événements HN

- 2008 - Les THATCamp (The Humanities and Technology Camp)

- 2011 - Day of Digital Humanities

- Organisations de nombreux hackatons, de journées d'étude, de colloques et d'universités d'été

Multiplication des taxonomies et des répertoires de méthodes

- Taxonomy of computational methods in the arts and humanities

- Digital Research Tools Directory (ou BambooDiRT)

- Taxonomy of Digital Research Activities in the Humanities (TaDiRAH)

- NeMO : NeDiMAH Methods Ontology

Le Digital Humanities Manifesto

Et dans le monde francophone ?

2010 - Le Manifeste des Digital Humanities

Juin 2014 - Fondation d'Humanistica

Autres initiatives

- Juin 2014 - Fondation, à l'Université du Montréal, du Centre de recherche interuniversitaire sur les humanités numériques

- Été 2017 - École d'été « Humanités numériques » - CERIUM

- Automne 2017 - Programme de DESS en édition numérique (UdeM)

- Automne 2019 - Programme « Culture et numérique » (UQTR)

Mais encore ?

[U]ne véritable historiographie nous fait défaut. L’histoire politique ne se réduit plus depuis longtemps à une histoire événementielle, ni l’histoire des sciences à la liste ordonnée des découvertes et des découvreurs. […] Le récit standard est aveugle à la diversité non seulement des domaines, mais aussi des pays et des zones linguistiques et culturelles. Notre vulgate n’est pas satisfaisante.

Aurélien Berra, « Pour une histoire des humanités numériques », dans Critique, vol. 8-9, no 818-819, p. 617.